|

- Home

- Barrio Chino: Chinatown in the Caribbean

Barrio Chino: Chinatown in the Caribbean

Chinese in Cuba

One of the CHCP members made a personal trip to attend the Overseas Chinese Festival (Festival de chinos de ultramar) in Havana, June 2-7, 1998. The purpose of this festival was to foster interchange of experiences between the Chinese in Havana’s Chino Barrio (Chinatown) and Chinese across the world. Over the years, the Chinese community in Cuba had lost the language and traditions of their ethnic origin and are reaching out to Chinese throughout the world to regain them.

Many people are surprised to learn that there is a Chinatown in Cuba, but Chinese have been a part of Cuba’s history since at least 1847. Although Chinese may have arrived in Cuba earlier, the first large group of Chinese arrived on the Spanish frigate Oquendo in 1847 to work on sugar plantations. When the ship dropped anchor in Havana harbor, only 206 of the original 300 contract laborers from Guangdong Province had survived to work the sugar fields.

These indentured workers and those who followed were recruited to fill the gap created by the termination of African slave trade. Estimates of this immigration over the next quarter century range from 50,000 to 130,000. About 13 percent died during the voyage or shortly after arrival.

These early laborers were bound to virtual slavery on the sugar plantations for four pesos a month. At the end of their eight year contract, the Chinese were often in debt to the plantation owners for food, clothes, and other daily needs.

Between 1860 and 1875, a second wave of Chinese immigrants arrived: about 5,000 who fled anti-Chinese sentiment and legislation in California. “The Californians,” as these relatively wealthy newcomers came to be called, laid the economic foundation of Havana’s Chinatown. At the same time, former indentured laborers provided an eager work force for produce farms, laundries, restaurants, small soy sauce and tobacco factories, and family businesses typical of Chinatowns across the globe.

Havana’s Chinatown became the largest Chinese enclave in Latin America. Throughout the 19th century, Chinese Cubans participated in the struggle to gain independence from Spain, which succeeded in 1898. A period of integration and assimilation followed.

A third wave of Chinese immigrants to Cuba resulted from the political and economic upheavals between the establishment of Sun Yat Sen’s republic in 1912 through the early years of the Chinese revolution. At its height, the ethnic Chinese population in Cuba was about 40,000.

Traditionally small business owners, many Chinese left Cuba with the dissolution of private enterprise in 1959. In time, this exodus, gradual assimilation, lack of new Chinese immigration and death of community elders led to the deterioration of El Barrio Chino. The Chinese Cubans are estimated at only about 500 today. Only a very small portion of Havana’s Chinatown is occupied by Chinese Cubans and their descendants. However, some Chinese chose to remain after 1959, and the younger generation now include doctors, lawyers and engineers. These young people, often the product of intermarriage with non-Chinese, are determined to regain their lost traditions.

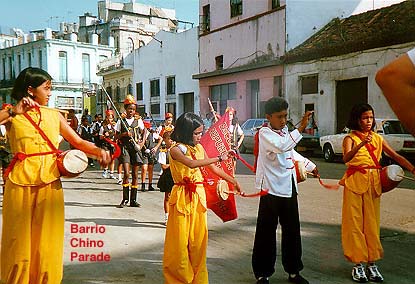

The Chinese Language and Arts school opened in 1993 and thrives today. Various community groups are working to revitalize Havana’s Chinatown and to rescue and foster Chinese traditions for future generations. Several years ago, Cuba’s economic policy was altered to allow individual operation of small businesses such as repair shops, beauty salons, and produce and food stands. Many such ventures are now active in the Havana Chinatown. After decades of attrition, the Chino Barrio community are experiencing a renaissance with a bustling market and plans for a museum and renewal of the historic architecture.

Our CHCP member brought gifts for the Chinatown community: two suitcases of books and videos on Chinese culture, including: donations from the Chinese Cultural Center in Sunnyvale, CHCP’s own Golden Legacy curriculum of Chinese cultures and traditions, Connie Young Yu’s Chinatown, San Jose, USA, a symbolic sequined Pearl of Wisdom and Dragon Gate from the Dragon Master Dave Thomas and CHCP. “The country is very poor,” she says. “The average Cuban earns $7 [U.S.] a month.” Responding to the need of the community, she left all of her personal belongings as well. Other recent donations from overseas Chinese included office equipment and cultural items such as incense, Chinese books and music…and 1,000 pairs of chopsticks.

While the government provides health care and there are many doctors, the country is hampered by lack of pharmaceuticals. Chinese doctors are introducing the use of acupuncture and massage to help alleviate this medical shortage.

Education in Cuba is free. About 90 percent complete high school and 70-80 percent go on to college. However there are not enough jobs for this highly educated population.

Despite their situation, our CHCP member reports that the people are cheerful and, in contrast to the usual Chinese reserve, the Chinese Cubans are very affectionate and demonstrative.

Resources:

- Coe, Andrew. Cuba. Hong Kong: The Guidebook Company Ltd., 1997.

- Navarro, Esperanza and Isabel Sierra. “The Chinese Presence.” Sol Y Son, no. 5, 1997,: 30-31

- Strubbe, Bill and Karne Walt. “Start with a Dream.” The World and I, September 1995, 188-197

- Twu, Rose-Marie. “El Barrio Chino.” Presented at Senior Citizens Meeting, King Recreation Center, San Mateo, July 1998.

- Wong, Bill. “Cuba’s Chinatowns: Tales from the Diaspora.” Asian Week, 9 April 1998.

A Comment by a CHCP Member

A Comment by a CHCP Member

On the Chinese that went to Latin America:

"Most were worked to death either in mines or sugar cane farms. As noted above, the availability of Chinese as indentured servants made them easy prey for the labor brokers since slavery was outlawed. Those that went to South America, the United States and Southeast Asia all came from the same part of China, a farming region near Canton where my family also came from. Until 1950 almost all the Chinese immigrants came from the Pearl River Delta Region.”

Chinese in Jamaica

Chinese in Jamaica

According to http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/History/Jamaica-history.htm:

"In 1645 the British captured Jamaica from the Spaniards…In 1670 Spain formally ceded the island to Britain. Two years later the Royal Africa Company, a slave-trading enterprise, was formed. The company used Jamaica as its chief market, and the island became a centre of slave trading in the West Indies…Settlers, using slave labour, developed the sugar, cocoa, indigo and later coffee estates...[before] the slave trade was abolished in 1807. After the emancipation of slaves in 1834, the plantations were worked by indentured Indian and Chinese labourers.”