|

- Home

- A Woolen Mills Chinatown Arch Jnl-2

A Woolen Mills Chinatown Archaeologist’s Journal -2

By Rebecca Allen, Ph.D.

Week of May 3, 1999: Surprises and Ceramics

Locating Ourselves in Space

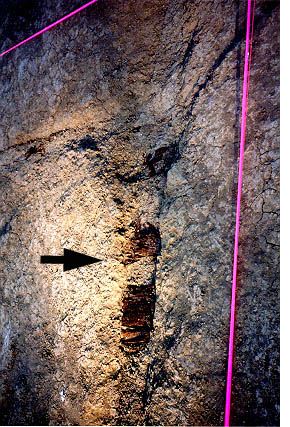

After our second week of field work, the archaeology crew has a good idea of the location of remnants of the Woolen Mills Chinatown. Building foundations, front porch piers, street layout, and other clues have tied us into the layout of the Chinatown. We’ve pieced together the puzzle of what’s left in the ground together with the historic maps, and it’s all (more or less) making sense. It’s sometimes hard to mentally picture buildings where we now only have bricks. Among the things we carry in our toolkit bags are nails and bright-colored string. With one corner, several tapes, quick calculations, and a hammer, we can string out where the buildings and yard areas once were, and suddenly what’s on the ground begins to come to life. City streets are once again visible, and the hot-pink string at least gives visitors and archaeologists alike a better idea of where in the town you’re standing when walking around the site.

Sewers and Outhouses

Long before sewer systems, many of California’s urban residents used the old-fashioned system of the outhouse that we now tend to associate with rural areas. Throughout the 19th and sometimes into the 20th century, town dwellers dug “privy pits” in their backyards. Workers known as “honey dippers” driving “honey wagons” would go through town and clean out the outhouses as needed. Eventually, though, outhouses had to be moved in the yard. When that happened, it provided homeowners with a pit that could be filled with household trash and debris. A hundred years later or so, these privy-trash pits become int eresting to archaeologists. We learn what people were eating, what they were eating from (ceramics, glassware), what they were playing (games, toys), smoking (pipes), and all other sorts of other insights into urban behavior. This is what we expected to find in the Woolen Mills Chinatown.

eresting to archaeologists. We learn what people were eating, what they were eating from (ceramics, glassware), what they were playing (games, toys), smoking (pipes), and all other sorts of other insights into urban behavior. This is what we expected to find in the Woolen Mills Chinatown.

Surprises

Local San Jose Chinese in the 19th century were determined to build this Chinatown. Some local politicians and other people in the City were determined that the Chinatown not be built, in large part due to racial stereotypes and prejudice. Contemporary newspaper accounts tell of some of the restrictions placed on the Chinese. On June 20, 1887, the San Jose Daily Mercury reported that “No buildings will be erected within 300 feet [of the nearest existing city streets] and Chinatown will not be visible from this thoroughfare…”. Five days later a city councilman informed the newspaper that he would try to declare a city resolution that the Chinese would have to hook into the town sewer that was at least 1000 feet away at their own expense, and that this would probably deter them. The Mayor declared this resolution “out of order.” To our surprise, the residents of the Woolen Mills Chinatown, with much labor, determination, and money, did hook into the main sewer system, possibly to deter local stereotypes of Chinatowns as dirty or unclean. We’ve been piecing together the remnants of an interesting and elaborate water supply and sewer system.

Backyard Trash

So, we’ve been finding less artifacts than what we originally anticipated, but the bits and pieces of what we are finding are fascinating. For example, although almost always broken, ceramic dishes that we find can clue us into diet, economy (what the residents could afford to purchase), and the importance of having familiar objects from China.

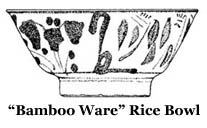

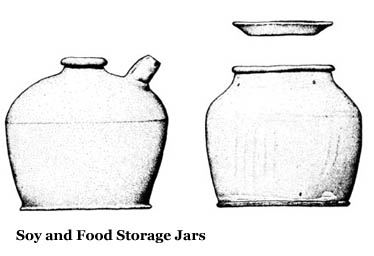

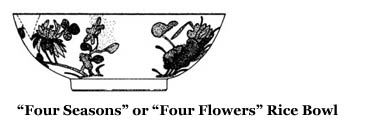

Chinese generally used individual rice bowls. Favorite patterns were blue-and-white porcelain. The one illustrated below is frequently referred to as “bamboo” ware. Food was served out of larger bowls, such as the Four Seasons or Four Flowers pattern, in a bright polychrome design (more than three colors). Some food and staples such as soy sauce came from China in brown stoneware jars.

Drawings: Courtesy of the California Department of Parks and Recreation |

|

|

Archaeologists use the pieces of ceramic pottery we find to help tell us about the past. The broken pieces, or sherds (the English call them shards), will be taken to the laboratory, where they’ll receive a good washing. Much like a picture puzzle, archaeologists will then try to fit together as many sherds as we can, so that we know the number, patterns, and shapes of what it is that we’re finding.

Forward to (Journal -3) Week of May 10, 1999: Field Photos Working with Caltrans are archaeological consultants from the firms of Past Forward, Inc., KEA Environmental, Inc., Foothill Resources, Inc., PAR Environmental, Inc., and the University of California, Chico. |